“There’s only one species that’s native to Africa. And it’s disappearing fast.”

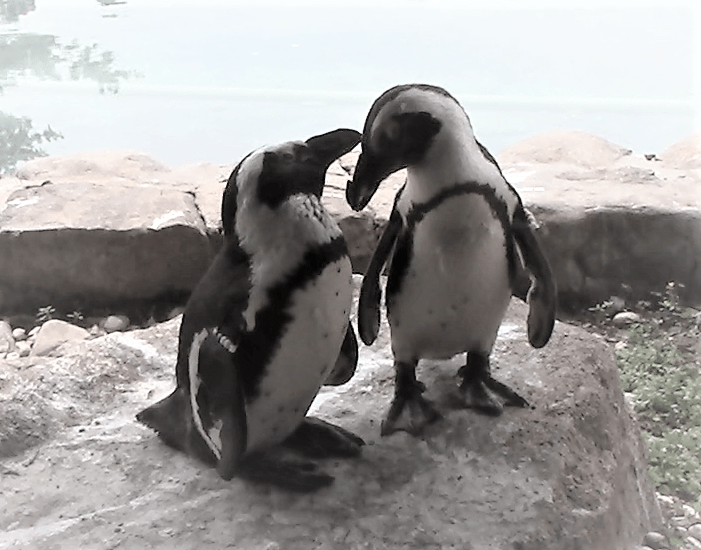

Photo by Kelsey Kehm.

I hate to break it to you, but you’ve been living a lie: most of the world’s penguins don’t live in Antarctica. Instead, they inhabit Australia, New Zealand, and South America. But there’s only one species that’s native to Africa. And it’s disappearing fast.

When I first started penguin research in fall 2016, the most recent estimate said that 30,000 breeding pairs of African penguins existed.

In January 2020 – less than three years later – that number slipped to 20,850. These penguins are edging closer to extinction every day.

Morgan blickley, undergraduate penguin researcher

The African penguin, also known as the Jackass penguin due to its donkey-like call, lives along the rocky outcroppings and sandy beaches of Namibia and South Africa [1]. This endangered species dines on anchovies, mackerel, and herring, all of which are heavily fished for human consumption [1].

Historically, the African penguin suffered decline due to human exploitation, as they were hunted for food and used as fuel for ship boilers due to their oil [1]. Plus, humans collected approximately half of all eggs laid in the early twentieth century for food and stripped penguins’ nests of guano, an important structural element for proper nest building [1]. Current threats to the African penguin include oil spills, habitat loss, and climate change [1].

African penguins are essential for both the environment and economy. In South Africa, the ecotourism movement has attracted over 500,000 visitors and generated about $2,000,000 annually, according to one study [2]. But more importantly, African penguins are a key part of the ecosystem, as they provide food for sharks, orcas, sea lions, leopards, and caracals [1]. In fact, they are so important that researchers call them an indicator species, since we can determine the overall health of the ocean by the penguin population [1].

My goal in writing this blog is to keep you, the general public, informed about recent research developments in the areas of population dynamics, mating and breeding, and conservation efforts for the African penguin. My hope is that with increased awareness, we can launch a stronger initiative to save this unique species.

References:

- Seiphetlho, N. L. African penguin. South African National Biodiversity Institute. 2014. Available from: https://www.sanbi.org/animal-of-the-week/african-penguin/

- Lewis, S.E.F; Ryan, P; Turpie J. Valuing an Ecotourism Resource: A Case Study of the Boulders Beach African Penguin Colony. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2011. Accessed from: Google Scholar.

CCC